Clashing value systems

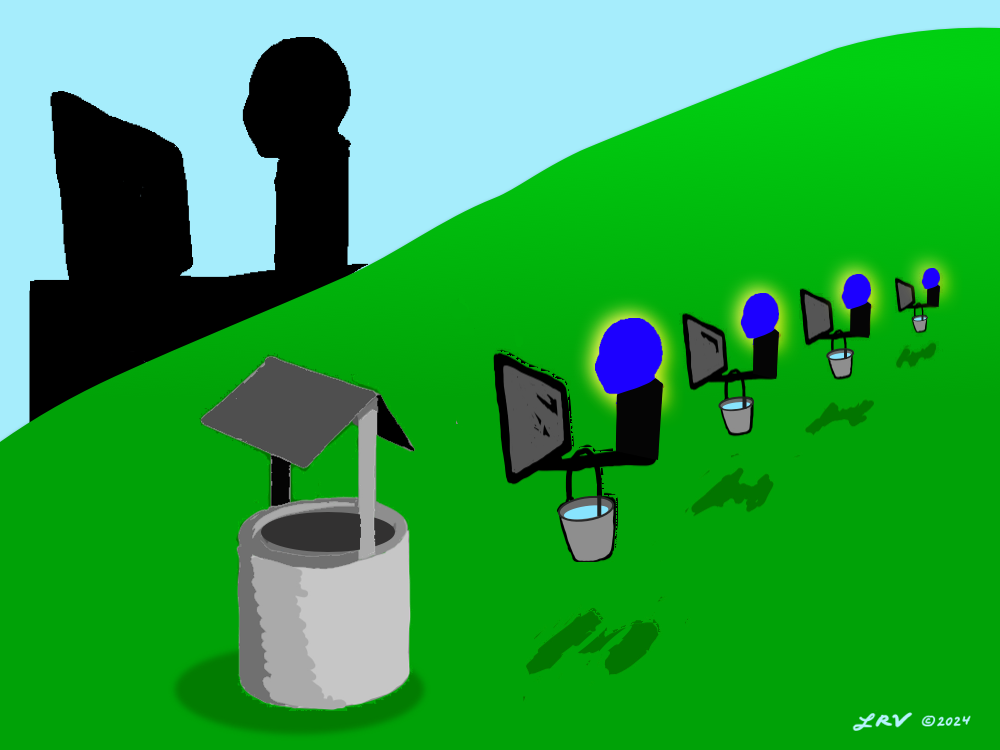

Now for the meaty part. Let's examine the disconnect between corporate tech culture and empathic connection.

A few observations

If you were to study this culture like an anthropologist, what would you see? You would see people who are motivated by intellectual and business challenges. Hard-working puzzle-solvers who are capable of impressive feats of engineering. You would also see a power hierarchy in which a select few are given formal power over others in exchange for playing out the function of management. Those who are skilled in the language of the group culture speak and act in a political manner emphasizing exchanges of social currency. “Team players” are those who mold themselves to suit their managers’ personalities and interests.

"Do you know when it’s time to do the right thing and when it’s time to follow orders?"

- general manager, initiating a conversation with an employee

The primary messages that are passed down the management stack are directives. Flowing in the opposite direction are various forms of compliance that validate managers’ authority and soothe their insecurities. A ritual plays out between managers and their subordinates in which the managers espouse narratives meant to suggest that psychological safety exists in the group’s decision-making. “Feel free to raise your concerns with me anytime so that I can address them” is a typical example. The real test of this narrative is assertive expressions of need that contrast with management's interests.

“Why do you care so much?”

- mid-level manager, in response to concerns about the firm’s management practices

You will also notice that some struggle to fit in. They find it hard to agree to the terms of the implicit psychological contract (Rousseau, 1995) that management enforces. One term codifies the transactional nature of their employment: members will give up autonomy in exchange for a paycheck. Another term highlights compliance: members will comply with orders even if they clash with members’ core values. Members are allowed to challenge managements’ ideas but not their decisions. And even that challenge may turn out to be a narrative courtesy that doesn’t apply in practice.

“Now we’re just bitching.”

- executive, in response to employees presenting findings that he dislikes

Humanity-disaffirming practices

In addition to the above, you will notice some troubling power dynamics. The psychologist Robert Cialdini might say that managers act as “compliance professionals” (Cialdini, 2007). They are rewarded for extracting willing compliance from their subordinates through the use of “weapons of influence” while furthering strategic goals set by their superiors. They are also rewarded for confidently espousing narratives that present the group and its leaders favorably to outsiders regardless of underlying realities.

“No news is good news.”

- mid-level manager, on actively soliciting feedback from subordinates

Because of the function of this role, personal qualities like arrogance, low empathy/EQ, and weak interpersonal communication skills are not necessarily gating factors. Effective engineer-politicians may be granted formal power over others with little regard for their understanding of human emotions or others’ relational needs. Productive narcissism is generally rewarded.

“There is no place for anger in the workplace."

“The next time you feel strong emotions, try not to show them as much.”

- new managers, commenting on their direct reports’ emotions

Note: on emotions in the workplace

One of my female colleagues mentioned that these last two quotes are in a sense good advice. Many women engineers have the early-career experience of crying at work (e.g. out of frustration or sadness) expecting to receive empathy and understanding. Instead, they find out that it cost them dearly in terms of status. This phenomenon is even more pronounced for men. For example, the author of these stories cried in the bathroom of a cafe across the street from his office for this very reason.

On this topic, I confidently point out that not being able to feel and express natural human emotions amongst colleagues at times of great distress indicates low psychological safety. Crying is a moment of vulnerability that gives others the opportunity to rally around the distressed team member, building a tremendous amount of trust and belonging in the process. We engineers like efficiency, right? Well, an emotionally intelligent response in these moments is absurdly efficient with respect to emotional processing and bonding.

Asking empathetic questions helps others to understand why the individual is distressed. The reason is often meaningful to the work and relationships of the group. By negatively branding those who express their emotions considerately and genuinely at work, we squander some of the most valuable opportunities for connection. It's that kind of connection that drives teamwork and makes our workplace a humane space.

"Never cry in front of male managers" is good advice in this culture. But that's not because there's something wrong with crying. It's because the management culture is toxic to human well-being. Period.

Empathy as a liability

We can now see how empathy might clash strongly with a corporate tech firm's management culture. Those who seek to advance their careers through people management must typically dismiss their empathetic instincts to (1) further strategic objectives and (2) align better with their managers. If their manager tells them to act in a way that would harm others’ motivation, belonging, trust, etc., it is advantageous to lack empathy in implementing those orders. Otherwise, the employee will be burdened by the weight of their conscience and function inefficiently as a corporate asset.

“That doesn’t count.”

- manager, dismissing his subordinates' leadership experiences to dissuade them from advancing in their careers

But what of emotional intelligence, which very notably includes empathy and social awareness? Research suggests that it is a critical leadership skill (Goleman, 2019). Some even go as far as to claim that EQ is a stronger determinant of leaders’ success than IQ and that the higher you are in an organization, the more important it is.

“You wouldn't hire a liberal arts major to do the plumbing.”

- division head, on engineers driving grassroots culture development initiatives

The problem is that EQ is difficult to cultivate in cultures that prioritize intellectual performance and compliance behaviors. Social-emotional awareness is seen as distracting from sustained analytical work. This puts the culture fundamentally at odds with various aspects of emotional intelligence. EQ deficiency is baked in.

“Stop asking these people questions and focus on your technical work!”

- director, yelling at a subordinate

“We should all feel comfortable yelling at each other and then grabbing a coffee afterwards.”

- (female) senior manager discussing workplace culture at a women's seminar